In a Law and Order rerun, Assistant District Attorney Jack McCoy, as usual, started with the presumption that the perpetrator freely chose to commit the murder. However, the defense lawyer rebutted that the subject’s genes gave him no choice. It was beyond his client’s control, invoking the nature side of the nature-nurture debate. Cognitive psychology adds interesting insights to the other side, nurture.

Nature-Nurture focuses on the causes of our behaviors. The mark of the debate is the distinction between genetic determinism (which cannot be overcome) and learned behavior (which can be chosen by reasoned behavior). That is the stark view. We now know that certain genetic traits are exhibited (or not) depending on the environment (nurture).

The discussion below focuses on the limitations of reasoning over learned behavior.

From the Wikipedia article on Nature-Nurture,

Nature is what we think of as pre-wiring and is influenced by genetic inheritance and other biological factors. Nurture is generally taken as the influence of external factors after conception e.g. the product of exposure, experience and learning on an individual.

On this site, the slow building on one’s mental worldview based on one’s experiences closely relates to decision making. Our neural brain reacts to experiences dependent on the presence or completion of critical periods. The result layers our knowledge into development stages which has a life-long effect on our decision making. Part of the influence results from knowledge being partitioned into certain, pretty sure, and accept because trusted authorities tell us it is so.

Critical Periods, Learning

Knowledge stages are marked by critical periods. During critical periods you develop personal behaviors and mental worldview that become the foundation for subsequent knowledge and decision making. Learning to see occurs during one such stage. You must learn to discriminate objects between the 3rd and 8th month. Infants born with cataracts unfortunately bear this out. If the cataracts are successfully removed before the critical period has ended, they will learn to see. Perform the operation when they have passed the critical period and they will never see properly. Yes, retina pixels will send the information into the brain’s occipital lobe but the neural connections are already set. These connections aren’t modified by new experiences.

Those skills developed during the visual critical period become the basis for all subsequent seeing. If one never forms the connections which combine edges of objects, visual processing will never advance even with complete optical information.

Behaviors with Critical Periods

- Physical skills. Walking, hearing, seeing, language use, motor skills.

- Social skill sets. Self-image, personal effectiveness, moral compass. Experimental evidence for social skill critical periods has not yet become a priority.

Critical Period Physical Markers

- Increased presence of the neuromodulator, gamma-Aminobutyric acid (GABA), in the vicinity of synapses.

- Start of critical period. GABA allows easier modification of the signal magnitude communicated between neurons. Modification of synapses is a mark of learning.

- End of critical period. GABA’s relative scarcity increases the difficulty for the synapse to alter with novel experiences. Modification can still occur but it requires a larger or more frequent occurrence of novel input to be learned.

- Myelination. Insulation about axons which carry signals to other parts of the brain

- Start of critical period. The axons which reach into other modules of the brain are not myelinated. Pre-myelination axons connecting separate computational areas of the brain (e.g. directly processed optical nerve output is sent to distinct modules that extract color information, object detection, movement, etc.) communicate their results with lots of noise and slowly. The different modules of the brain don’t know well what each other have experienced.

- End of critical period. The axons between brain modules commence being insulated, which increases the accuracy and speed that other modules receive the assessment made by the module.

Critical Periods, Progress across the Brain

- Myelination described here relates to cortical lobes.

- The basic rule is that myelination, the end of the critical period, starts at the back collar (about age 1) proceeding forward to the forehead (about age 25-30).

- Back Collar refers the back of the brain, to the occipital lobes, the sites of cortical enhancement of visual inputs. They myelinate earliest.

- Then , the temporal lobes and parietal lobes proceed in tandem.

- Temporal lobes process auditory input, which we occurs as infants and toddlers develop language. Understanding what was said and saying what they want.

- Parietal lobes, in the middle of the cortex atop the brain, connect the body and the cortex. It receives and processes bodily positions as well as sends signals to activate movements and speech.

- Frontal lobes, behind the forehead, have been identified as the lobes of advanced thinking. The executive functions like decision making and the initiation of responses to an individual’s needs, goals, and fears.

- Deep in the brain, those parts required for basic sustenance of the body are fully functioning at birth. This is much of the brainstem, the old brain, and the mid brain. Breathing, eating, and excretion do not need to go through a learning period. Such later learning as specific favorite tastes are modifications in satisfying the fundamental need, not changing the need itself.

- The limbic system, between the advanced cortex and the primitive brain structures, contains many important brain functions, including balancing one’s needs, goals, and fears (the results are emotions) . It also provides long-term memory necessary for learning the relationship between situation, action, and result. The hippocampus, the module for long-term memory formation, is known to start functioning between age 3-5. Prior to that age, learning dependent on non-immediate information does not occur.

Knowledge and Age

Decisions, when they are consciously made, are based on what we know, desire, and fear. Particular experiences occurring at certain ages (critical periods) allow our neural connections to change easily. Once the critical period is over, further change requires very large discrepancies in the new experiences to our previous learned lessons. More typical than change, the learned connections become the basis for the next stage. A strong sense of self learned at home is not destroyed by a bad first day at school, rather deprecation of the problem at school is more likely.

We weigh these factors according to our personal moral code, which has been formed layer-upon-layer as we grow from a dependent infant to a questing child into a youth stepping beyond the family up through adolescence, young adulthood into maturity.

Personal Knowledge

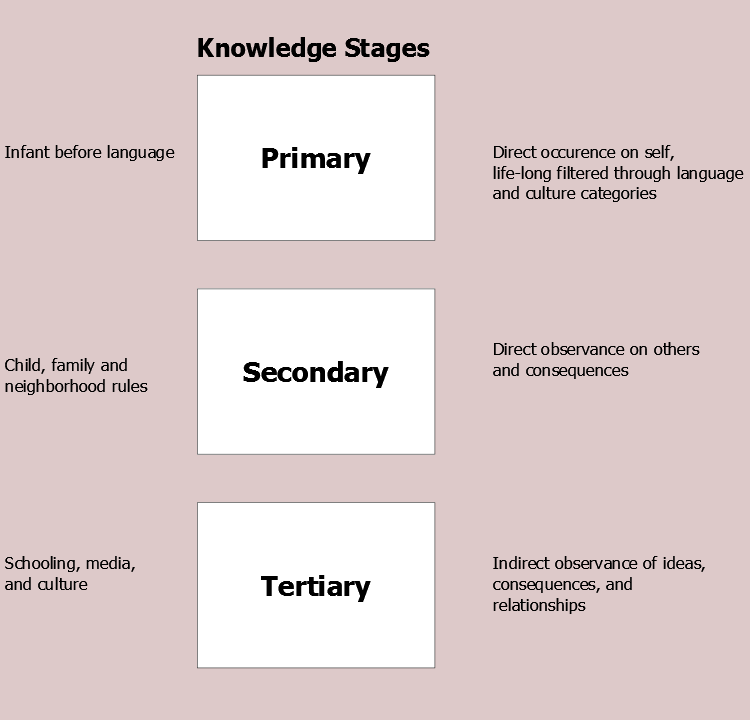

In the Knowledge Model shown in Figure 1, primary knowledge is that which we started learning as infants. At that time our morality is driven by pleasure and pain. We are just starting to understand the shapes, sounds, tastes, and feelings of day-to-day life. The knowledge stored, before we learn language, is direct interpretation our reactions and responses. We continue this immediate learning all through life, but as we learn words, the categories into which we place observables become those conventional categories that the language of our culture uses. The idiosyncratic notions of our earliest years get labels, perhaps ill-fitting, from newly learned words.

Second-Hand Knowledge

The secondary layer of knowledge (in Figure 1) commences in the family unit. We have mastered enough of language so that we begin to understand that other family members are describing their experiences. When we are not a part of the experience, but hearing their version of what happened, we are gaining secondary knowledge. We cannot be quite as sure of what we are told as what we experience, but we share many experiences with our parents and our siblings. We know how they describe things we are a party to, which gives us a measuring stick to apply to our second-hand experience of their actions.

In the secondary stage, learning is enforced by a new moral code. The proclamations of parents must be treated as good. Believing and acting on their moral code rewarded. Disagreement with them is bad and punished. The deeper primary value system of pleasure and pain continues, but it is buried underneath, affecting our receipt of their messages.

Academic and Authority-Based Knowledge

The tertiary stage is a convenience grouping of all learning and knowledge gained after we graduate from the family circle. Among our friends and peers, we are exposed to behavioral choices which are beyond the sanctions of our parents. In school, our teachers impart knowledge that we (mostly) have to accept on their authority. Some of that knowledge is merely conventional–reading, ‘riting, and ‘rithmetic–but other knowledge has moral tone, like democracy, helping others, good citizenry, independence, and respect.

A transition in morality occurs when a person realizes some peers come from families with different choices of right and wrong. Also, sets of laws from society and from church are taught, with the realization that all behavior is judged by applying these rules. Personal behavior and morality can now weighed by its position relative to distinct sets of rules.

Basics of Decision-Making

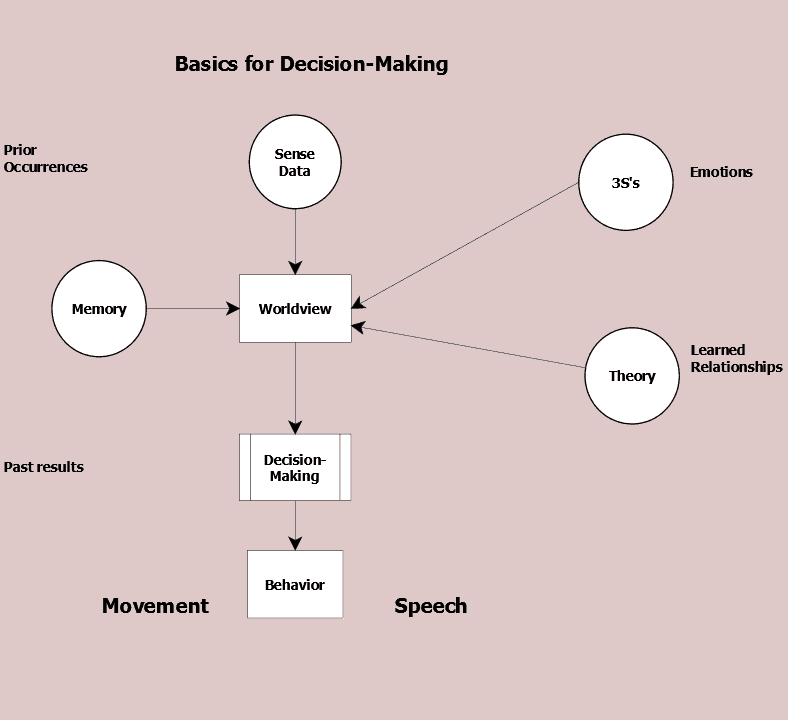

At the top of Figure 2 Basics of Decision Making, sense data enters into a person’s awareness. Since we already have our internal view of what the world is like and how things are related, this new sensory information is judged within that framework. We use memory, both of personal events and of learned knowledge, in performing the task. Our internal worldview uses knowledge to weigh the possibilities of satisfying our needs, desires, and fears. They originate in the fundamental 3S imperatives (genetic: satiety, sex, and safety) and with our experiences are molded into emotions, reflecting our satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the world as we see it.

We make decisions sometimes by logic and sometimes by association. The role of logic is easy to grasp. If the facts of the situation offer us a behavioral action which satisfies a need, desire, or allay a fear then we may choose it. Association is for those cases in which we don’t have sufficient facts or time to assess the facts, and we must make a decision at once. We choose from actions we took in prior similar situations that resulted in satisfactory results.

Conclusions

The main point of this post is that behavior is affected the sequence of our experiences. Even if we use perfect logic as an adult, if our earlier learning was flawed, our behavior can be odd or unusual. Our nurture is formed layer upon earlier layers. Learned beliefs in our early years are not replaced by later experiences. They shape the subsequent layers, created by subsequent experiences.

Ideas built into one’s worldview during the reward-punishment ethics of family circle are strong, yet the relation between actions and ethical value may match or not match the overall cultures value. When a person learns the society’s value, that layer fit into one’s worldview may be easy or may require mental contortions if they were raised by pickpockets.

One question has always bothered me. How did culture originate? How did the collection of approved behaviors and ideals we learn in society come into being? A likely hypothesis: culture is the fossilized behavioral choices of our cultural ancestors. Culture is the accretion of centuries of choices which served their originators, and society, well. Considering the vast number of individual choices made across a multitude of local situations, it’s a marvel that the culture still congeals.

At some early occasion, our ancestors were presented with a dilemma and hit upon a particular behavior, amidst the existing behavioral repertoire. The behavior’s success and the importance of the person making the decision led to its adoption as the standard way to approach the dilemma.

Decision Model How we choose

Internal Worldview Mental understanding

Reasoning: Logic and Association Deduction and induction

3S Imperatives, Emotions, and Consciousness Genetic steps to homo sapiens

Nature-Nurture and Free Will Determinism and free will

Culture Origins Example from the art world