Each person experiences a different slice of the same total physical reality. None of us know all of it, yet we assume it is the same as the part we experience. Our mindset is built from stimuli into concepts. The effect of our localized experience imprints uniquely on each one of us. The decisions we make and the behaviors we perform are based on our internal understanding of what external reality is. The formation of our mindset (I also call this, our internal worldview) is crucial for understanding how we think, choose our actions, words, and behaviors.

Our shared genetic heritage gives us the sensory receptors to automatically, before consciousness, fill and complete missing external information. For instance, our visual space is populated by complete objects–I see many cars in a parking lot, I don’t see many fragments of cars–although none of them are completely in my view. Also our internal worldview is not exclusively sensory, it is also organized by our needs, desires, and fears. The sources of these non-tangible aspects of our worldview are constructively explained in Brain through the Ages and Development to the Adult Mind.

Although, as humans, we have a broad genetic commonality, there are specific individual differences, like neural threshold levels, which idiosyncratically mold the way sensory data is categorized.

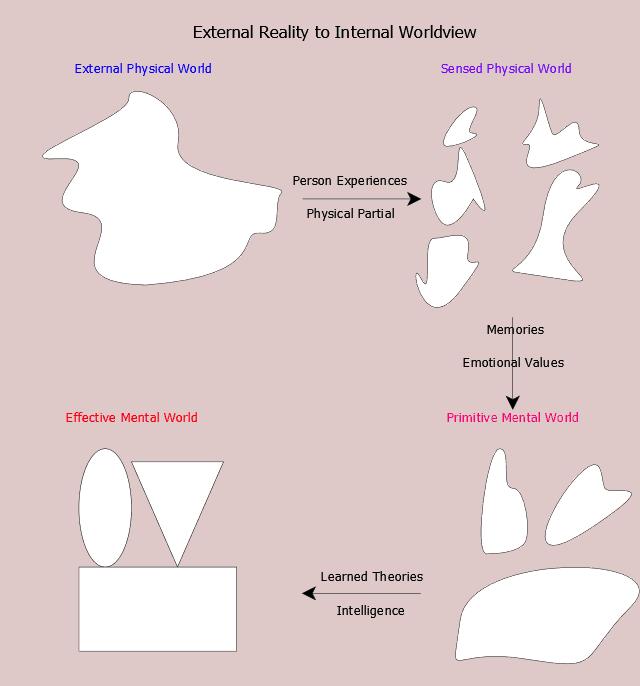

At a high level, Figure 2.1 captures, three distinct steps from sensory data to an adult’s mindset. Our perception of the external world goes through three stages as we deal with daily challenges. This initial depiction of the path goes clockwise from the top left. It’s much simplified to expose major features. Later essays develop the stages further as well pre-adult aspects, but let’s consider this figure first.

External Physical World

In the upper left of Figure 2.1, the outside, external world is complete and connected. It is vast and mostly unavailable to any single one of us, yet each of us assume that the pieces we perceive are reflective of the overall world. (This point of view projection lies at the core of many objective-subjective debates.) Since we each perceive unique portions of reality, we each project unique totalities of reality. That’s all very abstruse at this time. My flash fiction story, “Alien Sofa” presents an easy-to-digest example.

Philosophers may argue about whether the world exists or is just imagined in one’s mind. I’m not a philosopher. I’m more pragmatic. Solipsism, that everything occurs within one’s mind, can remain in philosophic tomes.

Sensed Physical World

The initial neural response, upper right, is to categorize the data obtained via individual senses and send these incipient categories further into the brain for enhancement.

As I’ve emphasized, the portion of that complete reality we see is often incomplete. It is also disconnected, not logically connected. Would it surprise you to learn that only 30-100 of the many millions of bodily impulses traveling up the spinal cord make it beyond the brainstem to the brain’s upper chambers? It’s true and even that limited number is further weaned by the limbic system, according to our needs, desires, and fears. Only a select few signals, from the spinal cord, reach our frontal cortex and our conscious attention.

Of course, information from cranial senses – sight, audio, taste, and odor – comes more directly to the cortex. That data is significantly enhanced by our cortical processing. In this stage, the emphasis is extracting objects in our local environment.

As will be mentioned many times, the neural threshold (the magnitude of electrical potential a neuron’s dendrites must deliver to cause it to fire) is not a single, set value for all humans. It is a range. Since we individually can have a unique neural threshold, that provides another avenue by which we may perceive things differently, in the event two of use experience the same reality slice.

Primitive Mindset

In the lower right of Figure 2.1, we develop our primitive mindset. Before cranial sensory data is available for conscious consideration, it is further accumulated with combined information. A person looks at the sensed physical world and using their needs, desires, and fears assess the physical facts for utility. These stored memories and traits result from the limbic system merging the 3S Imperatives–Satiety, Sex, and Safety–onto the sensed physical reality. These new, augmented and abstracted categories simplify analysis by removing information not germane to a person’s interests. The collection of the resulting categories are labeled a situation.

The current situation is inductively compared against remembered situations. One of our needs may be satisfied in a particular remembered situation while other needs aren’t. In other words, the emotional valence, effect of choice on one’s needs, desires, and fears, of a particular situation rarely satisfies completely. This is the start of the explanation to why we often feel conflicted in our choices.Effective Mindset

Until this point, the path from external to internal (in Figure 2.1) is the same for man as for lower animals. Now though in the lower left, we subject the categorized data to assessment by our higher intellect, both by similarity to experience and by logic. Other mammals are restricted to similarity by experience. With learned knowledge, we smooth and link our situations and their component categories together. Our knowledge and presumptions about relationships between categories creates a tidier, more effective mindset worldview upon which we will base our actions.

With our knowledge incomplete and our understanding of interconnections imperfect, we may enforce consistency and logic only within limited domains of our worldview. That’s a source of cognitive dissonance. An example of domains with scope is an individual whose warm and sincere in personal dealings yet ruthless in business transactions.

Iterative

For simplicity I’ve shown processes in Figure 2.1 as uni-directional, actually there is a rapid interchange of preliminary recognitions that are shared across the various, simultaneously occurring sensory and memory processes. For instance, a first impression in the sensed physical world which promises to satisfy completely the sexual imperative can direct attention back to specific areas of the external physical world for further details right away.

Related Interest

Thought Train Length. Another discreteness in thinking